Archiwum - 11. Festiwal Filmowy Pięć Smaków

Bede Cheng: rekonstrukcja nie polega na poprawianiu wad filmu

O cyfrowej rekonstrukcji filmów opowiada Bede Cheng z L'Immagine Ritrovata – laboratorium, w którym powstały nowe wersje "Made in Hong Kong" Fruit Chana, włączonego w tym roku w sekcję gatunkowej klasyki, czy "Lepszego jutra" Johna Woo i "Dotyku zen" Kinga Hu, prezentowanych w programie 9. Pięć Smaków.

Emilia Skiba, Pięć Smaków: Spotykamy się w hongkońskim biurze L'Immagine Ritrovata. Jak doszło do tego, że włoska firma specjalizująca się w cyfrowej rekonstrukcji filmów otwarła swoje laboratorium także w Hongkongu?

Bede Cheng, L'Immagine Ritrovata Asia: Siedziba firmy mieści się w Bolonii, we Włoszech, ale w 2008 roku otrzymała do rekonstrukcji pierwszy film z Azji Południowo-Wschodniej. Był to "Konfucjusz" z 1940 roku, zlecony przez Hongkońskie Archiwum Filmowe. Od wtedy liczba azjatyckich filmów spływających do L'Immagine Ritrovata zaczęła rosnąć. W 2008 roku pracowałem dla Międzynarodowego Festiwalu Filmowego w Hongkongu, jednak pojechałem na letni kurs FIAF w Bolonii, poświęcony rekonstrukcji, gdzie poznałem osoby z tej branży. Ponieważ liczba zlecanych filmów z Azji wciąż rosła, pomysł na otwarcie laboratorium także tutaj był tylko kwestią czasu. Jest ono mniejsze, ale wyposażone w specjalistyczny skaner, więc klienci z Azji Południowo-Wschodniej – Hongkongu, Tajwanu, Singapuru, Filipin, Korei – nie muszą już wysyłać oryginalnych materiałów do Włoch. To bardzo praktyczne rozwiązanie, a dzięki temu rośnie też zainteresowanie rekonstrukcją. W Europie czy Stanach rekonstrukcja cyfrowa nie jest już tak nowym pomysłem, ale tutaj dopiero ją odkrywamy. Sprzyja tu jednak zainteresowanie komercyjnym potencjałem starszych filmów.

Jak wygląda praca w takim laboratorium?

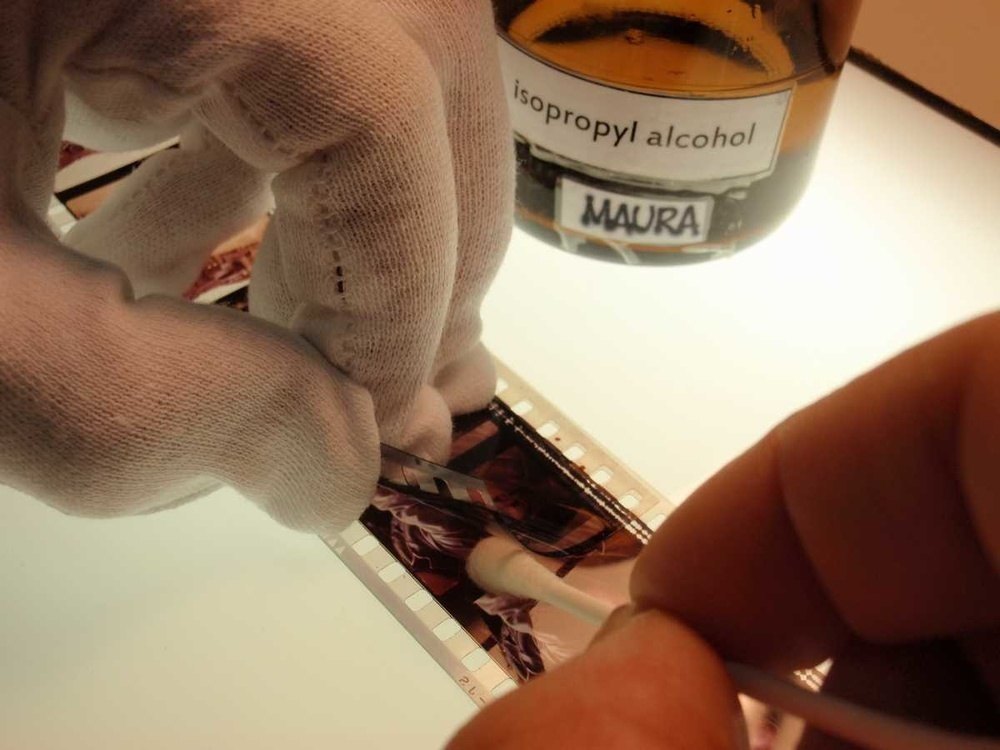

Tu wykonujemy pierwszy etap rekonstrukcji, odpowiednio przygotowujemy oryginalne materiały do dalszych prac. Kiedy przyjeżdża do nas film, naprawiamy uszkodzenia, czyścimy zabrudzenia oraz skanujemy, by uzyskać cyfrowy obraz oryginału. Pliki z obrazem przenosimy później na dysk, który przesyłamy do Włoch do dalszych prac.

Co obejmują dalsze prace?

Z filmu usuwa się elementy, których tam oryginalnie nie było: wszelkie zanieczyszczenia, kurz, zarysowania, pleśń – której tak naprawdę nie da się usunąć, ale mamy sposoby, aby ją pokryć. Celem tych prac jest przywrócenie filmu do pierwotnego stanu albo najbardziej go przypominającego.

Kim są wasi klienci? Wspominałeś, że wasze zlecenia w większości pochodzą od firm azjatyckich.

Tak. To firmy producenckie, archiwa filmowe. Czasem też prywatne osoby. Są również reżyserzy, którzy chcieliby, aby ich film został zrekonstruowany. Ale to nie tylko świat filmu. Zdarzył się na przykład bank, który chciał scyfryzować swoje filmy czy starszy pan, który chciał zrekonstruować film ze swojego wesela sprzed trzydziestu lat.

Czy promujecie rekonstrukcję? Na przykład gdy macie kontakt z archiwami filmowymi?

Jak najbardziej. Bierzemy też udział w targach filmowych takich jak Filmart. Ponieważ włoska L'Immagine Ritrovata funkcjonuje na rynku od 1992 roku, ważną częścią naszego wizerunku są referencje. Zdążyliśmy już ugruntować swoją pozycję w tej branży. Oczywiście bywają sytuacje, gdy film powierzany jest nam dopiero po jakimś czasie od pierwszego kontaktu, a współpraca wymaga czasu.

Uważasz, że poziom zaufania do idei rekonstruowania filmów wzrasta?

Tak i nie. To czasochłonny proces. Ale zauważyłem, że coraz więcej zainteresowania rekonstrukcją jest na Tajwanie. Niektóre z odrestaurowanych tajwańskich klasyków, jak "Dotyk zen" czy "Dragon Inn" Kinga Hu, były prezentowane w sekcjach dedykowanych klasyce na dużych festiwalach takich jak Cannes i zyskały po nich bardzo dobrą prasę. Te dwa filmy rekonstruowaliśmy w L'Immagine Ritrovata. Ogólnie rzecz ujmując, wiele instytucji zdaje sobie sprawę, że może to być doskonały sposób na promocję kultury, historii i dziedzictwa ich kraju.

Ile czasu zajmuje przeciętny proces odrestaurowania filmu?

Zwykle trwa to od czterech do sześciu miesięcy. Zdarza się, że dłużej, jeśli materiał jest bardzo zniszczony. Przykładem trudniejszej i bardziej wymagającej rekonstrukcji był "Made in Hong Kong" Fruit Chana. Film powstawał praktycznie bez funduszy, a reżyser sklejał różne negatywy jako materiał, na którym kręcił. Wciąż bardzo łatwo zauważyć zmiany kolorów między poszczególnymi segmentami, które z tego wynikają. U nas potwierdził to dodatkowo proces skanowania materiałów, które otrzymaliśmy. Skaner ustawiamy zależnie od typu filmu, po to, aby odpowiednio odczytał materiał. To jednak bardzo czułe urządzenie i po zmianie typu filmu w "Made in Hong Kong" po prostu się zatrzymywał. Musieliśmy więc programować go od nowa na kolejną rolkę. Mieliśmy też przypadki filmów z Filipin, które były bardzo zabrudzone. Sam proces czyszczenia, a później skanowania takiego materiału zabiera sporo czasu.

Co masz na myśli mówiąc "sporo czasu" w przypadku skanowania?

Optymalnie to jedna klatka na sekundę. Ze względu na wysoką czułość skanera zdarza się, że trwa to dłużej. Jeśli pracujemy z trudniejszym filmem, poświęcamy więcej uwagi samemu nadzorowaniu tego procesu.

Jakie wyzwania stawia rekonstrukcja poza tymi, które dotyczą pracy bezpośrednio w laboratorium?

Najtrudniejsze jest pozyskanie wszystkich materiałów, na bazie których w ogóle możemy zacząć pracę. Czasem otrzymujemy film, w którym brakuje różnych fragmentów. Zdarza się, że nasi klienci sami czasem nie wiedzą, gdzie można szukać brakujących elementów. Kompletowanie tych materiałów może trwać latami.

Ile filmów rocznie odnawiacie?

Około piętnastu. Jeszcze zanim powstało laboratorium w Hongkongu, L'Immagine Ritrovata odrestaurowała filmy Bruce'a Lee czy "Lepsze jutro" Johna Woo.

Wcześniej pracowałeś dla festiwali. Na pewno masz swoją osobistą listę filmów, które odrestaurowałbyś w pierwszej kolejności?

Muszę zaznaczyć, że jako laboratorium świadczymy tylko usługi, nie odrestaurowujemy kopii, by zajmować się dystrybucją. Ale tak, moja prywatna lista filmów byłaby bardzo długa. Zacząłbym od hongkońskich filmów z lat osiemdziesiątych, aby ocalić je zanim zaginą wszystkie materiały, na bazie których można by je zrekonstruować.

Zdarzyły ci się sytuacje, gdy na przykład rekonstrukcję zlecał producent, ale sam reżyser oponował taką decyzję, bo po latach uważał, że zrobił słaby film?

Nie, to się nie zdarzyło. Ale mamy inne wyzwania. Filmy nakręcone cyfrowo łatwo można poddać obróbce, po której wyglądają bez skazy. Niektórzy reżyserzy zdążyli już zapomnieć, że kręcąc na taśmie nie da się uniknąć niedoskonałości, na przykład niektóre ujęcia będą rozmyte. Celem rekonstrukcji nie jest poprawianie takich wad.

Jaka przyszłość czeka rekonstrukcję filmów, również w kontekście zmian technologicznych?

Sama rekonstrukcja nie jest końcowym produktem. Może zdarzyć się, że odnajdzie się nowy materiał źródłowy i film można zrekonstruować na nowo, przy użyciu nowej technologii, która na pewno będzie lepsza i prostsza w obsłudze. Niemniej, żywotność dysków to raptem kilka lat, więc film jest niezmiennie najbezpieczniejszym nośnikiem. Nigdy nie wiadomo, kiedy dysk przestanie działać, a przecież to kiedyś musi nastąpić. Stąd zachęcamy naszych klientów, by równolegle produkowali interpozytyw na taśmie 35mm, jeśli mają odpowiednie warunki, by go przechowywać. To najtrwalszy sposób zachowania filmu, taśma przetrwa nawet sto lat. Pamiętam entuzjazm, który towarzyszył przejściu dystrybucji na dyski cyfrowe. Wydawało się, że to takie tanie. Ale to złudzenie, bo dysk działa zaledwie kilka lat, podczas gdy taśma przetrwa o wiele więcej.