Archiwum - 11. Festiwal Filmowy Pięć Smaków

Ann Hui: Między kinem hongkońskim a światowym

Ann Hui w 2017 roku obchodziła siedemdziesiąte urodziny. Jej długa kariera w przemyśle filmowym, zdominowanym przez twórców młodych, co więcej – najczęściej mężczyzn, sprawia, że jest postacią wyjątkową zarówno w Hongkongu, jak i w wymiarze globalnym. Wnosi kobiecy punkt widzenia reżyserki z powojennego pokolenia filmowców. Retrospektywa w ramach 11. Azjatyckiego Festiwalu Filmowego Pięć Smaków, prezentująca filmy z każdej dekady twórczości Ann Hui, podkreśla wkład autorki w kino światowe. Ukazując ewolucję prac reżyserki, dokumentuje także transformację kina hongkońskiego – od czasów rebelianckiej energii niesionej przez nową falę po obecny wkład w kino Chin kontynentalnych.

Ann Hui była jedną z pierwszych osób w gronie hongkońskich filmowców, którzy kręcili w Chińskiej Republice Ludowej na początku lat 80. i do dziś realizuje filmy po obu stronach granicy. Dwadzieścia lat po przejęciu przez Chiny rządów w Hongkongu, jej twórczość ilustruje dualistyczny proces "ukontynentalnienia" kina Hongkongu i "hongkongizacji" filmów w Chińskiej Republice Ludowej. Jeśli szukać wątków, które łączą filmy Ann Hui z różnych dekad, ważną pozycję zajmuje tu autorski styl kładący nacisk na historie opowiedziane z perspektywy kobiet, rozwarstwienia czasowe, wielopoziomowe kompozycje wizualne, ekstremalne kąty widzenia, kwestie amnezji, pamięci i traum. Jednak poza wyjątkowością spojrzenia, kariera Ann Hui dowodzi, jak istotne w świecie filmu są sieci zależności – ruchy takie jak hongkońska nowa fala, ale też międzynarodowe festiwale i system studyjny, pozwalające ponadnarodowym autorom takim jak Hui rozwijać swoją wizję.

Ann Hui – w szczególności z punktu widzenia kobiet pracujących w środowisku, nierzadko jawiącym się jako klub tylko dla mężczyzn – reprezentuje grupę filmowców, którzy wyrwali hongkoński przemysł filmowy ze stagnacji, do jakiej doprowadził zdominowany przez mężczyzn system praktycznego uczenia się zawodu. Zapoczątkowali czasy, w których przewagę zapewniło wykształcenie akademickie (Ann Hui ukończyła University of Hongkong, HKU, gdzie sama obecnie pracuję) oraz dalsze studia w Europie czy Ameryce. Hui i pozostali autorzy, których kinowe debiuty przypadły na rok 1978 i 1979, początkowo tworzyli w raczkującej telewizji hongkońskiej, pod kuratelą producentki Seliny Chow, będącej również absolwentką Wydziału Anglistyki na HKU. To dzięki współpracy Seliny Chow i Sylvii Chang – wówczas dopiero wschodzącej gwiazdy chińskiego kina – powstała firma producencka, która odpowiadała za debiutancką "Tajemnicę" (The Secret, 1979) Ann Hui. Postać grana w nim przez Sylvię Chang prowadzi śledztwo związane z oskarżeniem syna sąsiadów o makabryczne podwójne morderstwo. "Tajemnica" zapoczątkowała hongkońską nową falę, otwierając kobietom wiele drzwi w przemyśle filmowym. Praca reżyserki ze scenarzystką Joyce Chan zaowocowała filmem, w którym śledztwo oparte na faktach prowadzi kobieta, a świeżość i dynamikę zapewniła w nim nielinearna narracja skupiona na bohaterkach meandrujących między światem chińskich przesądów i problemami kolonialnej współczesności, uosobionymi tu przez policję. Pod koniec lat siedemdziesiątych dało to Ann Hui głos tak w świecie filmu, jak i hongkońskim społeczeństwie.

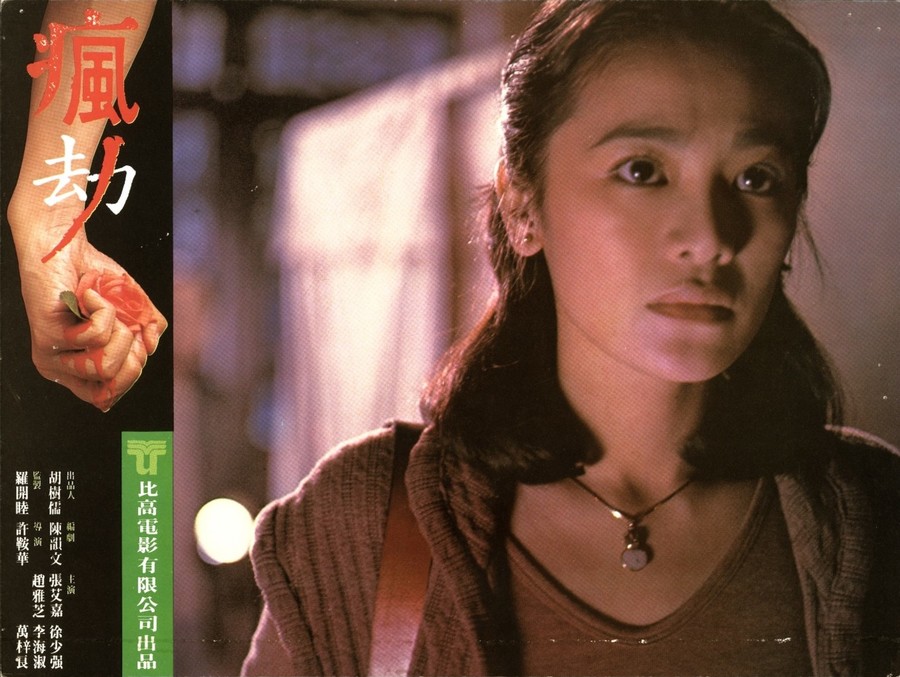

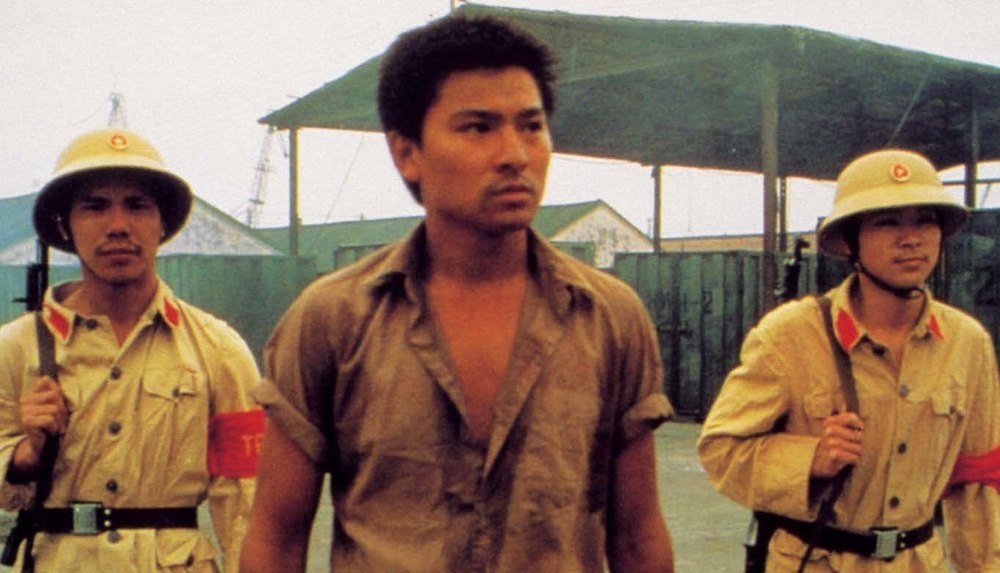

W "Boat People. Uchodźcach z Wietnamu" (Boat People, 1982) autorka czerpie z tematu podjętego jeszcze podczas pracy w telewizji. Dla wielu uchodźców z niestabilnego politycznie i gospodarczo Wietnamu, zjednoczonego w 1975 roku, pierwszym azylem był Hongkong. Ann Hui przeniosła opowieści uciekinierów na mały ekran w dokumencie "Below the Lion Rock: From Vietnam" (1979), a do kin temat wprowadziła filmem z Chow Yun-fatem w roli głównej, "The Story of Woo Viet" (1981). Napływ uchodźców wzrósł po wojnie chińsko-wietnamskiej z 1979 roku, gdy wielu etnicznych Chińczyków zasiliło szeregi byłych żołnierzy armii Południowego Wietnamu i ich rodzin oraz amerykańskich sojuszników i sympatyków z Zachodu. Możliwość oficjalnego zrealizowania w Chinach pierwszej większej hongkońskiej produkcji – pospołu z "Klasztorem Shaolin" (Shaolin Temple, 1982) z Jetem Li – napłynęła do Ann Hui sama. By uzyskać pozwolenie na zdjęcia na przypominającej Wietnam wyspie Hajnan, reżyserka musiała zagwarantować, że wroga Chinom Socjalistyczna Republika Wietnamu zostanie ukazana w negatywnym świetle. Kino hongkońskie było wówczas mocno uzależnione od rynku tajwańskiego, kontrolowanego przez silnie antykomunistyczny i nacjonalistyczny Kuomintang (KMT), w związku z czym żaden film wyprodukowany w Chinach, włącznie z "Boat People", nie miał szans na pokazy w Republice Chińskiej (Tajwanie). Zważywszy jednak na precyzję, z jaką Ann Hui przekazuje traumatyczne historie opowiedziane jej przez uchodźców w Hongkongu, film staje się krytyką systemu komunistycznego jako takiego, a autorytaryzm rządu wietnamskiego zlewa się z lokalizacją w Chińskiej Republice Ludowej, gdzie zrealizowano zdjęcia. Co więcej, ta właśnie (mylna) interpretacja filmu wciąż wybrzmiewa w Hongkongu, w którym unosi się niepokój związany z przejściem spod rządów brytyjskich pod kontrolę Chin.

Wówczas zresztą nadszedł moment, by alegorycznie uchwycić niepokoje społeczne. W 1982 roku Margaret Thatcher odbyła w Pekinie spotkanie z Deng Xiaopingiem, związane ze statusem Hongkongu, z którego wyszła niepewnym krokiem, prawdopodobnie dogłębnie wstrząśnięta, oraz ogłosiła negocjacje, zakończone ostatecznie chińsko-brytyjską umową w 1984 roku, traktującą o polityce "jednego kraju, dwóch systemów" i całkowitym przekazaniu kolonialnego terytorium, począwszy od powrotu Hongkongu do Chin w 1997 roku, a skończywszy na integracji z kontynentem w 2047. Ze względu na wizytę Thatcher oraz fakt, że wielu mieszkańców Hongkongu wyemigrowało z Chin i Wietnamu z powodów politycznych, ekonomicznych czy religijnych, "Boat People" trafiło do kin bardziej jako dystopijna parabola przyszłych rządów komunistycznych Chin niż jako traktat o nacjonalizmie, krytykujący wietnamskie zapędy na wojnę z Czerwonymi Khmerami wspieranymi przez ChRL. Obraz dopełnił cykl filmów Ann Hui obecnie znanych jako "Trylogia wietnamska", a pomimo tego, że zdaje się bardziej komentować relację Hongkongu i Chin niż reperkusje konfliktów w Wietnamie, w których udział brały Francja, Stany Zjednoczone i Chiny – niezmiennie wzburzył emocje podczas festiwalu w Cannes w 1983 roku. Tytuł został wycofany z konkursu głównego pod naciskami rządu francuskiego, który starał się ocieplić swoje stosunki z byłą kolonią, stąd jego pokazy odbyły się poza główną sekcją. Międzynarodowa prasa podchwyciła jednak historię kontrowersyjnego filmu oraz młodej, uzdolnionej reżyserki z Hongkongu. Niezależnie od chłodnej relacji z samym festiwalem i problemów z dystrybucją na rynkach chińskojęzycznych, Ann Hui przetarła szlaki w kontaktach z Chinami kontynentalnymi oraz zaistniała w międzynarodowym obiegu festiwalowym i świadomości dziennikarzy na całym świecie, którzy wciąż piszą o jej twórczości.

"Letni śnieg" (Summer Snow, 1995), "Tacy jesteśmy" (The Way We Are, 2008) oraz "Proste życie" (A Simple Life, 2011) reprezentują kolejne dekady Ann Hui. Od końca XX wieku, przez milenijny przełom i od początku XXI wieku jej filmy portretują miasto w oczekiwaniu na rok 1997 i powrót do Chin oraz dwie pierwsze dekady Hongkongu jako Specjalnego Regionu Administracyjnego (HKSAR). Reżyserka przygląda się mu z perspektywy starzejących się kobiet i ich zmagań z rozłamem pokoleń, łatwo zauważalnym w pogrążonym w wiecznym pędzie mieście. Dbałość w ukazywaniu szczegółów codziennego życia mieszkańców Hongkongu spaja filmy autorki, przynosząc portrety rodzin z klasy robotniczej, średniej i wyższej – widziane przez pryzmat kobiecych doświadczeń.

"Letni śnieg", którego chiński tytuł można przetłumaczyć jako "Czterdziestolatka", ukazuje bohaterkę uwięzioną między obowiązkami rodzinnymi – opieką nad owdowiałym teściem cierpiącym na zaawansowanego Alzheimera i wychowaniem syna – a karierą w świecie poddanym szybkim procesom globalizacji i cyfryzacji. W roli głównej wystąpiła Josephine Siao, ukochana przez publiczność aktorka dziecięca, której karierę spowolniła utrata słuchu, a jej wkład w film przyniósł jej Srebrnego Niedźwiedzia na 45. Berlinale. To ugruntowało też pozycję samej Ann Hui w kręgu festiwali europejskich. Roy Chiao wciela się z kolei w rolę teścia – byłego żołnierza KMT, cierpiącego na demencję, która przynosi wspomnienia z czasów wojny z Japończykami. Amnezja eliminuje jednak w jego wspomnieniach zimną wojnę, a śmierć mężczyzny kładzie kres niepoprawnym politycznie powiązaniom rodziny, tuż przed zmianą władzy w roku 1997. Angielski tytuł filmu oddaje sprzeczne odczucia, jakie towarzyszyły tej zmianie, wyrażając cień optymizmu, który zakłada, że zaradni Hongkończycy przetrwają w każdych warunkach, nawet jeśli chińskie rządy przyniosą ochłodzenie. Reżyserka uwierzytelnia także wizję wdowca, kreując scenę, w której kamera z góry portretuje bohaterów spoglądających na białe płatki niesione gorącym letnim wiatrem. Ta poetycka wizja służy za metaforę końca czasów kolonialnego Hongkongu, a jednocześnie obietnicę i wyraz niepewności związany z nagłym zaburzeniem cyklu przyrody ujętym w ramach prawnych "jednego kraju, dwóch systemów".

"Tacy jesteśmy" (The Way We Are) ponownie portretuje kobietę w średnim wieku, która nawiązuje głęboką relację z już starszą osobą. Tym razem Kwai (Pai Hei-ching) z trudem wiąże koniec z końcem wykładając towar w supermarkecie, a jej sytuacja rodzinna – jako wdowy pochodzącej z klasy robotniczej – jest daleka od ugruntowanej pozycji bohaterki z klasy średniej z "Letniego śniegu". Kwai początkowo lituje się nad starszą od siebie sąsiadką, nazywaną Babcią (Chan Lai-wan), która właśnie wprowadza się obok. Ich relacja szybko przekształca w silną, ponadpokoleniową więź, bazującą na odrzuceniu ze strony awansujących społecznie rodzin biologicznych, które już nie potrzebują starzejących się kobiet. Przykładowo Kwai trudno zmusić się do odwiedzania w szpitalu chorej matki, gdyż wizyty wzbudzają w niej poczucie wstydu jako dziecka, które zostało w tyle, pracując w fabryce. Mimo że to jej zarobki zapewniły dwóm braciom lepszą edukację i awans, ona sama utknęła w ślepym zaułku prostych prac. Babcia z kolei próbuje nawiązać relację z wnukiem, ale jej zięć stawia mur, unikając obarczenia się opieką nad starszą kobietą, która w dodatku przypomina o jego zmarłej pierwszej żonie. Tradycyjnie konfucjański patriarchalizm zawodzi bohaterki, których więź opiera się o klasę i płeć zamiast pokrewieństwa. Puentę w filmie tworzą obchody święta Środka Jesieni, symbolizującego zjednoczenie rodziny. Ann Hui przedstawia je jako otwarte wydarzenie, gromadzące lokalną społeczność – sąsiadów wspólnie celebrujących przy pełni księżyca i lampionach, którzy symbolicznie zburzyli ściany izolujące ich w małych mieszkaniach wielkich blokowisk.

Akcja filmu "Tacy jesteśmy" rozgrywa się w Tin Shui Wai, miasteczku wybudowanym w obrębie Nowych Terytoriów, które miało wchłonąć ubogą klasę robotniczą Hongkongu. Społeczność portretowana przez reżyserkę zaprzecza jednak łatce "miasta smutku", którą przyszyli Tin Shui Wai politycy i media, donoszące przez lata o kolejnych morderstwach, samobójstwach, przedawkowaniach i handlu narkotykami. Tin Shui Wai było często pierwszym przystankiem imigrantów przybywających z Chin, wiedzionych chęcią poprawy losu w Hongkongu, co z drugiej strony niekoniecznie stawało się budulcem opowieści o solidarności i zaufaniu. Ann Hui wykorzystuje w filmie realistyczne ujęcia nakręcone kamerą cyfrową, a całość staje się przymiarką do jej kolejnego filmu osadzonego w Tin Shui Wai, "Noc i mgła" (Night and Fog, 2009).

Filmy te stworzyły dyptyk, a nazwa lokalizacji spaja je także w chińskich wersjach tytułów. Warto podkreślić, że "Tacy jesteśmy" to film stricte fabularny, który posługuje się obserwacyjnym stylem jedynie po to, by wiernie oddać codzienną rutynę i zagłębić się w towarzyszące jej emocje. "Noc i mgła" jest jego przeciwieństwem. Film bazuje na szczegółowej analizie materiałów o prawdziwych zdarzeniach, opierając się na sławie Simona Yama, misternej strukturze inspirowanej "Obywatelem Kane" i melodramatyzmie wstrząsającej historii kobiety z Chin kontynentalnych, która po ślubie zostaje sterroryzowana i zamordowana razem z dwoma córkami przez psychotycznego męża. Mimo że bohaterki w "Tacy jesteśmy" są marginalizowane przez swoje rodziny, nie stają się ofiarami przemocy jak kobiety w "Nocy i mgle". Choć akcja drugiego filmu jest w dużej mierze osadzona w schronisku dla kobiet, tu kobiece więzi zawodzą i nie stanowią ochrony nie tylko przed przemocą domową, ale całą niewydolnością systemu opieki społecznej, który wymusza na imigrantkach pozostanie w dysfunkcyjnym małżeństwie, by ich rodziny przetrwały w Hongkongu. Reżyserka celowo odwołuje się w angielskiej i chińskiej wersji tytułu do "Nocy i mgły" (1955) Alaina Resnais’a, kreśląc symboliczne powinowactwo między hongkońskimi instytucjami opieki społecznej, przyzwalającymi na przemoc domową, a nazistowskimi obozami koncentracyjnymi, w których ofiary zwyczajnie i po cichu rozpływały się w "nocy i mgle" zaplanowanej przez Hitlera eksterminacji.

"Noc i mgła" częściowo rozgrywa się w Syczuanie, w przygranicznym Shenzhen, co podkreśla rosnące powiązanie twórczości Ann Hui z Chinami kontynentalnymi po wejściu w życie umowy o bliższej współpracy gospodarczej (CEPA) z 2003 roku, która ułatwiła filmowcom z Hongkongu pracę na kontynencie. Te związki wybrzmiewają jeszcze silniej w "Prostym życiu" (A Simple Life, 2003), który autotematycznie włącza okoliczności powstania tej produkcji jako część fabuły. Film opowiada historię relacji, jaka łączyła producenta Rogera Lee (w jego postać wcielił się Andy Lau) i jego starszą już wiekiem gosposię, Chung Chun-tao (Ah Tao), graną przez Deanie Ip, która po zawale nie może wykonywać swojej pracy, a życie zmusza ją do przeniesienia się do domu opieki.

"Proste życie" portretuje współczesne realia hongkońskiego przemysłu filmowego, dając wgląd w pracę Rogera – przedłużające się wyjazdy służbowe do Pekinu, wymuszenie na nim udziału w niewygodnych zabiegach o pozyskanie większych funduszy od bankiera, rozmowy o budżecie z podejrzanym inwestorem, groźby związane z brakującymi tysiącami dolarów, które zniknęły z konta czy tłumaczenie, że gwałtownie spadająca liczba widzów wskazuje, że film to porażka. Zważywszy na fakt, że grający Rogera Andy Lau jest także producentem wykonawczym filmu, warto podkreślić, jak autotematyczne są sceny, w których prowadzi on negocjacje z Yu Dongiem, prawdziwym szefem firmy produkcyjnej Bona Group. Lau, którego kinowym debiutem była rola w "Boat People", tym razem zatrudnia Ann Hui jako reżyserkę w swoim nowym projekcie. Andy Lau i Deanie Ip wystąpili wcześniej razem w "The Unwritten Law" (1985), do którego powstały jeszcze dwa sequele. Wyraźnie da się wyczuć, jak doskonale zgrany jest to duet, a chiński tytuł filmu, "Starsza siostra Tao" (Tao jie), podkreśla fikcyjne pokrewieństwo i bliskość między gosposią w podeszłym wieku a młodszym pracodawcą. Poruszająca postać, jaką wykreowała Ip przyniosła jej prestiżową nagrodę Volpi Cup na 68. Festiwalu Filmowym w Wenecji, gdzie "Proste życie" miało też swoją premierę.

Poza Andym Lau i Deanie Ip w filmie występuje nowofalowy reżyser Tsui Hark, a w epizodach pojawiają się takie legendy hongkońskiego kina jak Sammo Hung, Anthony Wong, Chapman To, Lawrence Lau czy świetnie rokujący młody chiński reżyser Ning Hao, a gościnnie nawet Raymond Chow, Roberta Chow, John Sham, Gordon Lam, Stanley Kwan, Andrew Lau i Angelababy. W ten sposób "Proste życie" spaja trzy ważne sieci powiązań, kluczowe dla kariery Ann Hui: krąg twórców nowofalowych, inwestorów z kontynentu finansujących koprodukcje chińsko-hongkońskie oraz świat festiwali filmowych, którego przykładem jest Wenecja. "Proste życie" otrzymało szereg innych nagród, w tym La Navicella Award (za "humanistyczne wartości"), Equal Opportunities Award (dosł. Nagroda Równych Szans), czy Wyróżnienie Specjalne przyznane przez katolicką organizację SIGNIS. Tym samym Ann Hui czerpie korzyści z rozbudowanej sieci powiązań w branży filmowej, która łączy chińskie fundusze z hongkońskim doświadczeniem oraz europejskim kapitałem kulturowym wyrażonym przez obieg festiwalowy.

W "Prostym życiu" reżyserka ponownie podejmuje swój stały temat – proces starzenia się i instytucji społecznych. W "Letnim śniegu" duża część akcji rozwija się wokół poszukiwania odpowiedniego ośrodka dla chorych na Alzheimera, a sam film zarzuca społeczeństwu hongkońskiemu obarczenie już i tak przepracowanych kobiet odpowiedzialnością za opiekę nad osobami starszymi. Podobnie jest w "Prostym życiu", gdzie koleje losu Ah Tao dają szczegółowy wgląd w funkcjonowanie zinstytucjonalizowanego systemu opieki nad starszymi Hongkończykami. Wraz z przeprowadzką świat Ah Tao rozrasta się, a Ann Hui wykorzystuje to, by zobrazować działanie domu opieki jako komercyjnej firmy i stworzyć portret mikrokosmosu hongkońskiego społeczeństwa. Podobnie nakreśliła zależności, w jakich funkcjonują kobiety pracujące – w odniesieniu do rodziny i innych instytucji społecznych – w filmach „Tacy jesteśmy” oraz „Noc i mgła”. Dzięki starannie dopracowanym ujęciom rozegranym w korytarzach, oknach i lustrach, reżyserka ukazuje swoje bohaterki jako kobiety uwięzione w mieszkaniach komunalnych, schroniskach, szpitalach, domach opieki, biurach i innych miejskich przestrzeniach, które sankcjonują ich cierpienie ze względu na płeć.

Deanie Ip kreuje kolejną niezwykłą postać w najnowszym filmie Ann Hui, "Nadejdzie nasz czas" (Our Time Will Come, 2017) – ponownie jako kobieta uwięziona w sytuacji, nad którą nie ma kontroli. Wciela się w rolę matki członkini ruchu oporu w czasach wojny chińsko-japońskiej. W jednej z pierwszych scen Ann Hui obrazowo nakreśla postać graną przez Deanie Ip, gdy każe jej najpierw wyłożyć na talerz trzy biszkopty i chwilę później schować do pudełka ten, który miałby być dla niej samej, a tym samym ukazuje gościnność kobiety wobec wynajmujących u niej mieszkanie uchodźców. Reżyserka to doskonała obserwatorka nawet najdrobniejszych szczegółów życia rodzinnego, a podkreślanie wagi jedzenia, gościnności i poświęcenia kobiet koresponduje z pokrewnymi scenami w filmach "Tacy jesteśmy" (grzyby), "Noc i mgła" (papryczki chili) i "Proste życie" (ozorki). Roger Lee ponownie pełni funkcję producenta, pod egidą firmy Bona, która odpowiadała też za "Proste życie". Ann Hui cementuje swoje powiązania z chińską i europejską nową falą – poprzez zaangażowanie w film montażystki Mary Stephen, która pracowała z Erikiem Rohmerem, oraz operatora Nelsona Yu Lik-waia, wieloletniego współpracownika Jia Zhangke.

"Nadejdzie nasz czas" podejmuje tematy, które stanowiły także oś poprzedniego filmu reżyserki, "Złoty wiek" (The Golden Era), tytułu zamykającego Festiwal Filmowy w Wenecji w 2014 roku. W obu przypadkach Ann Hui pracowała z chińskimi twórcami, by upamiętnić historyczne postacie związane lewicową inteligencją sprzed roku 1949. "Złoty wiek" to hołd złożony pisarce Xiao Hong, która zmarła w Hongkongu podczas japońskiej okupacji, zaś "Nadejdzie nasz czas" jest swoistą kontynuacją tej historii poprzez działania bohaterek – Fang Lan (Zhou Xun) i jej matki (Deanie Ip) – które pomagają pisarzowi Mao Dunowi (Guo Tao) i jego żonie w ucieczce z okupowanego Hongkongu. Filmy łączy nie tylko czas i miejsce akcji, ale również wykorzystanie stylu opowiadania ze "Złotego wieku", gdzie wywiady z fikcyjnymi bohaterami kreśliły ramy narracyjne w postaci serii retrospekcji. Tu rolę tę pełni historia opowiadana przez Bena, granego przez weterana hongkońskiego kina, Tony'ego Leung Ka-faia, który opowiada Ann Hui o swoim zaangażowaniu w dzieciństwie w działania Brygady Dongjiang (Wschodniej Rzeki). Przed okupacją Ben był uczniem Fang, teraz jego opowieść stanowi lojalne świadectwo jej wkładu w ruch oporu.

Podczas gdy inne filmy z Chin kontynentalnych portretujące walkę z japońskim okupantem opierają się na męskich bohaterach, Ann Hui na pierwszy plan wysuwa rolę kobiet oraz kreśli wpływ okupacji na ich codzienne życie. W wielu produkcjach podejmujących tę tematykę Hongkong jest też marginalizowany, zaś "Nadejdzie nasz czas" i "Złoty wiek" stawiają go na pierwszym planie, podobnie jak wcześniejsze produkcje studia Shaw Brothers oparte na prozie Eileen Chang, "Love in a Fallen City" (1984) samej Ann Hui oraz "Ostrożnie, pożądanie" (2007) Anga Lee.

Wielu twórców wplata osobiste historie w swoje filmy i Ann Hui nie jest wyjątkiem. Przykładem jest tu na poły biograficzny film "Song of the Exile" (1990), w którym Maggie Cheung wciela się w Hueyin. Dziewczyna powraca do Hongkongu po studiach filmowych w Londynie i musi wypracować na nowo relację z matką, z pochodzenia Japonką, która poślubiła Chińczyka w czasie wyzwolenia Mandżurii. Ze względu na to osobiste powiązanie z historią Japonii i Chin, reżyserka nierzadko powraca do czasów wojny, która stanowiła tło dla związku jej rodziców i z wyczuciem oddaje zawiłości decyzji, przed jakimi stają bohaterowie uwikłani w historię. Przykładowo, w "Nadejdzie nasz czas", sportretowana zostaje relacja japońskiego oficjela i narzeczonego Fang, który działa jako szpieg w siedzibie wroga. Więź między mężczyznami zacieśnia się podczas rozmów o twórczości poety Su Dongpo (Su Shi), a sam film nie rozpamiętuje imperialistycznego okrucieństwa tylko po to, by podsycić chiński nacjonalizm. Tu bohater ruchu wyzwoleńczego Blackie Lau (Eddie Peng) przystawia kolaborantowi do gardła nóż albo oddaje salwę celnych strzałów w bardziej introspekcyjnych momentach filmu. W twórczości Hui nie ma miejsca na nacjonalistyczny szowinizm, mimo że autorka miała swój wkład w kilka filmów powiązanych z zakończeniem kolonialnej epoki w Hongkongu, w tym epicką produkcję Xie Jina, "Opium War" (1997), zrealizowaną, by uczcić powrót Hongkongu do Chin.

Najnowszy film Ann Hui zbiega się czasowo z dwudziestą rocznicą funkcjonowania Hongkongu jako Specjalnego Regionu Administracyjnego Chińskiej Republiki Ludowej, a skoncentrowanie się reżyserki na wspólnej historii ruchu oporu, która łączy Hongkong z kontynentem, podkreśla tę relację.

Tematy, w które zagłębia się Ann Hui, sięgają jednak głębiej. Ponownie opowiada o matkach i córkach, miłości, weselach, kobiecej przyjaźni, rodzinnych zobowiązaniach, a także o codziennych zmaganiach, mających zapewnić syty obiad i rodzinną bliskość. Autorka wykorzystuje swoją reżyserską pozycję, by przekazać punkt widzenia kobiet i ich wspomnienia oraz dogłębnie przyjrzeć się społeczeństwu i jego instytucjom, które kształtują kobiece doświadczenia. Począwszy od "Tajemnicy", aż po "Nadejdzie nasz czas", bohaterki Ann Hui podejmują działania w sferze publicznej, nie tracąc przy tym związku ze sferą domową, prywatną. Silne międzygraniczne powiązania reżyserki i doskonała znajomość chińskiej diaspory gwarantują tę samą wnikliwość niezależnie od tego, czy Ann Hui kreśli charakterystykę Hongkończyków, Chińczyków z kontynentu czy chińskich migrantów. Perfekcyjnie uchwycone obrazy fascynujących kobiet, połączonych wspólną sprawą i walczących o sprawiedliwość dla swoich sąsiadów, rodzin oraz siebie samych, mogą równie dobrze stworzyć portret Ann Hui jako reżyserki. Dzięki karierze, która zapewniła jej pozycję wytrawnej autorki i międzynarodowo poważanej reżyserki, ma ona możliwość opowiadania historii kobiet marginalizowanych i spychanych na dalszy plan – które z pełną siłą wybrzmiewają tak w Hongkongu, jak wśród widzów na całym świecie.