Archiwum - 11. Festiwal Filmowy Pięć Smaków

Nansun Shi: młodych filmowców interesują hongkońskie tematy

Producentka Nansun Shi, zaangażowana w filmy takich jak "Lepsze jutro" Johna Woo i "Proste życie" Ann Hui, opowiada o zmianach, jakie zaszły w hongkońskim kinie od końca lat 70. i jego współczesnej tożsamości w kontekście rynku chińskiego.

Emilia Skiba, Pięć Smaków: Twoje wykształcenie nie jest związane z kinem. Jak trafiłaś do przemysłu filmowego?

Nansun Shi: Życie przynosi niespodzianki. Skończyłam studia, bo typowi azjatyccy rodzice oczekują, że będziesz lekarzem czy prawnikiem. Ja ukończyłam statystykę i informatykę, żeby uszczęśliwić rodzinę. Ale gdy wróciłam do Hongkongu, wiedziałam, że nie jest to praca dla mnie. To był rok 1975, a informatycy spędzali cały dzień sam na sam z komputerami w klimatyzowanym biurze. To do mnie po prostu nie pasowało. Po kilkuletniej nieobecności w Hongkongu chciałam zrozumieć społeczeństwo szybciej i zaczęłam pracę dla firmy zajmującej się public relations. W 1976 w Hongkongu odbywał się konkurs Miss Universe, a jedna z lokalnych stacji telewizyjnych szukała kogoś, kto dobrze znał języki i mógłby spędzać z kandydatkami dzień, a wieczorem relacjonować to w programie telewizyjnym. Ktoś mnie po prostu wtedy polecił. Sprawdziłam się w tej roli, później przyszły kolejne zlecenia z telewizji, a na koniec ktoś zaproponował, abym zaczęła tam stałą pracę. Nieco później, w 1978 i 1979, w Hongkongu nastąpił wysyp debiutów młodych, obiecujących twórców. Zaczęła się nowa fala. Wtedy ponownie ktoś zaproponował mi pracę, tym razem oznaczało to przejście z telewizji do produkcji filmowej. Tak trafiłam do firmy, która nazywała się Cinema City i miałam wielkie szczęście, bo wkrótce zaczęła lokalnie odnosić spore sukcesy, a ja zdobyłam doświadczenie w ekspresowym tempie.

Jaka panowała wówczas atmosfera w hongkońskiej branży filmowej?

To były czasy nowej fali, gdy debiutowało kilkudziesięciu reżyserów. Pojawiły się też nowe tematy. Uchodźcy z Wietnamu, nowe podziały klasowe powstałe po wojnie, ale także nowa lokalna tożsamość kulturowa, która przyszła razem z popularnością telewizji i Canto-popu. Ludzie chcieli oglądać filmy o bohaterach wzorowanych na sobie, a takie właśnie były produkcje Cinema City. Byliśmy wtedy bardzo dumni z naszej kultury, chcieliśmy więc oglądać nasze własne filmy i słuchać kantońskich piosenek. Branża skoncentrowała się na lokalnej kulturze.

Branża musiała być wówczas bardzo inkluzywna?

Zgadza się. Ale tak było zawsze. Ostatecznie Hongkong jest bardzo mały i nie mamy wystarczających zasobów ludzkich. Stąd tyle profesjonalistów z innych krajów w hongkońskim filmie – Sylvia Chang, Michelle Yeoh, Brigitte Lin. Te aktorki mówiły innymi dialektami, a później były dubbingowane.

Twoja niezwykła kariera obejmuje blisko cztery dekady. Co zmieniło się w branży filmowej z twojej perspektywy?

Od wczesnych lat 80. do początku 90. hongkońskie filmy miały się świetnie. Zaistniały też na rynkach międzynarodowych. Był to także moment, gdy spopularyzowały się kasety wideo, a to stworzyło popyt na jeszcze większą liczbę produkcji. Swoją drogą, zrobienie filmu wtedy nie było tak proste jak dziś. Dziś można nakręcić film choćby na telefonie. Tak czy inaczej, hongkońskie filmy obiegły wówczas świat, w tym były pokazywane na festiwalach takich jak Berlinale. Mój pierwszy film trafił tu do programu w 1982. W obiegu były też kasety, w zasadzie wszędzie. W sklepie na Sunset Boulevard w Los Angeles była cała sekcja z filmami z Hongkongu, podobnie przy Polach Elizejskich w Paryżu.

To były inne filmy niż te, które oglądała publiczność w Hongkongu?

Nie, to te same tytuły. Filmy wielkich reżyserów jak Tsui Hark czy Ann Hui, z gwiazdami jak Jackie Chan czy Sammo Hung. Choć trafiały się i bardziej artystyczne filmy. Sami dystrybutorzy szukali jednak kina rozrywkowego, które docierało do szerokiej publiczności. To one przyniosły hongkońskiemu kinu rzeszę wiernych fanów. Jednak w latach 90. stało się ono ofiarą swojego własnego sukcesu. Zaczęły się kiepskie filmy. Ale wciąż było ich jakieś 300 rocznie, co jest ogromną liczbą jak na tak małą lokalizację. Publiczność trudno zbudować, ale stracić można ją w mgnieniu oka. Hongkońskie filmy zaczęły tracić na popularności, bo spadła jakość produkcji. Filmów było za dużo i spora część kiepska. To był czas, gdy Hongkończycy zaczęli migrować do Kanady, Stanów, Australii. Wśród nich filmowcy. Wątpiliśmy w przyszłość hongkońskiego kina. To był jednak też czas przejścia Hongkongu pod administrację Chin i zaczęliśmy robić filmy na kontynencie. Na początku nie było tam ani rynku, ani widzów. Wszystko było archaiczne. Były na przykład stare kina z setkami miejsc, ale nikt do nich nie chodził. Ludzie oglądali filmy z pirackich kaset. Na początku Chiny oznaczały dostęp do zasobów, nie rynku, bo ten po prostu nie istniał. Na przykład w 2002 roku box office w Hongkongu wynosił około ośmiuset milionów dolarów i taka sama liczba była dla Chin, które są przecież dużo większe. Moja pierwsza produkcja w Chinach zdarzyła się jeszcze w 1992 i kręciliśmy na kontynencie ze względu na zasoby. Chcieliśmy mieć scenę na pustyni, była pustynia. Chcieliśmy kręcić w pałacu – był tam prawdziwy stary pałac. Reformy przemysłu filmowego zaczęły się dopiero w 2001-2002 roku. Wcześniej były tylko studia zarządzane przez państwo, które ograniczało liczbę filmów do stu rocznie, nie było funduszy. Studia zarabiały sprzedając kopię filmu bezpośrednio kinu. Nie było systemu dystrybucji, prawa autorskie kina zyskiwały wraz z zakupem fizycznego nośnika. Mając więc taśmę, miało się prawa autorskie i film można było grać do woli, dopóki nośnik na to pozwalał.

Co wydarzyło się w 2001 roku?

Rząd chciał rozbudzić przemysł filmowy, zdawano sobie sprawę, że kino jest tu bardzo zacofane, chciano je skomercjalizować. Po pierwsze, zniesiono regułę, która narzucała realizację koprodukcji tylko ze studiami zarządzanymi przez państwo. Po drugie, kina mogły mieć też prywatnych właścicieli, więc pojawiły się nowoczesne obiekty, w tym multipleksy. Także w dystrybucji mogli pojawić się ludzie z zewnątrz. Wnieśli ekspertyzę w zakresie tego, jak zarządzać nowoczesnym kinem czy obiegiem kopii. To była wielka zmiana, bo praktycznie każdy mógł teraz wejść w koprodukcję z Chinami. Od 2003 roku chiński box office rósł co roku w dwucyfrowym tempie. Zwolnił dopiero w 2015 i 2016, gdy wzrost był już tylko jednocyfrowy, zdaje się, że było to 3.7%. W 2003 roku sal kinowych było raptem dwa tysiące, a w zeszłym roku było ich już ponad czterdzieści tysięcy. Przez wiele lat Chiny produkowały po sto filmów rocznie, teraz jest ich siedemset. To bardzo sprzyjający okres. Wielu profesjonalistów przeprowadziło się więc do Chin. Ale niezależnie od kryzysu w latach 90., w ciągu ostatnim czasie widzę wzrost produkcji reżyserowanych przez młodych twórców, których interesują lokalne tematy. Te filmy cieszą się popularnością. Nie sądzę, żebyśmy mieli szanse na powrót do statusu kina hongkońskiego z lat 80. i 300 produkcji rocznie. To swoją drogą nawet nie było normalne. Był to moment, gdy Chiny i Tajwan produkowały bardzo mało, więc dało to szansę Hongkongowi. Ale historii nie można zawrócić. Rynek chiński znacząco urósł i nadal będzie się rozwijać.

Jak więc opisałabyś aktualną kondycję hongkońskiego kina?

Mamy teraz dobry trend, który uosabiają nowi, młodzi twórcy zinteresowani lokalnymi, bardzo hongkońskimi tematami. Trwa on już od kilku lat, a filmy te radzą sobie bardzo dobrze.

Takim filmem jest na przykład "Dziesięć lat"?

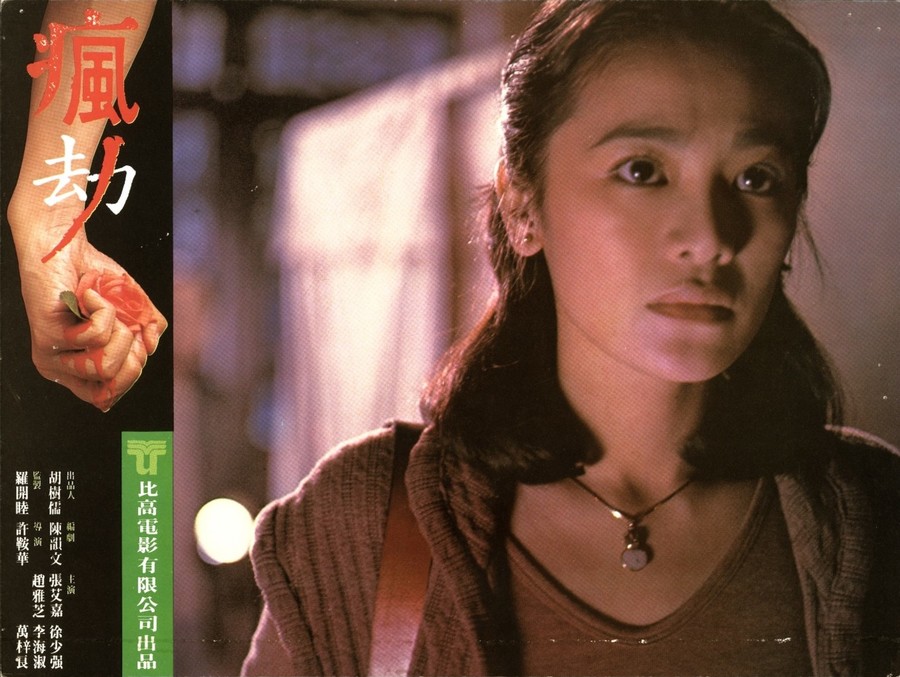

Nie sądzę. To osobny przypadek. Nie był to za dobrze zrobiony film. Był raczej wypowiedzią polityczną. W dodatku jeden z polityków, konserwatysta, zaczął mocno krytykować film. Wtedy ludzie zwrócili uwagę na ten tytuł, inaczej może by tylko przemknął. Mnie raczej chodzi o filmy takie jak "Rigor Mortis" Juno Maka, "Little Big Master" Adriana Kwana czy "She Remembers, He Forgets" Adama Wonga. To były dobrze zrobione filmy i odniosły też sukces komercyjny. Zeszłoroczne nagrody Golden Horse Awards były też znacznym sukcesem dla Hongkończyków. Wong Chun został nagrodzony jako najlepszy nowy reżyser za swój "Obłąkany świat", a obie aktorki z filmu "Zapiski z przyjaźni" Dereka Tsanga wspólnie wyróżniono za rolę pierwszoplanową. Obaj dopiero zaczynają swoje kariery.

Wspominałaś też o technologii. Jak wpłynęła na twoją pracę?

Technologia zmieniła bardzo wiele i sama nieustannie się zmienia. Ma to swoje wady i zalety. Ja na przykład nie muszę się już martwić, ile mamy w zapasie taśmy filmowej. Ale z drugiej strony cyfrowo powstaje tyle dubli, że proces ich selekcji staje się uciążliwy.

A jeśli chodzi o pracę reżyserów?

To bardzo zależy od osoby. Niektórzy są bardziej zorientowani na technologię niż inni. Jedni lubią eksperymentować, podczas gdy inni kręcą raczej tradycyjnie. Oczywiście, cyfryzacja zmieniła obraz i dźwięk, ale nie wpłynęło to na rzeczy takie jak sposób opowiadania historii czy ustawianie kadrów. Są reżyserzy, którzy dużo eksperymentują z 3D, podczas gdy Ann Hui kręci filmy bardzo tradycyjnie, czego przykładem jest "Proste życie", do realizacji którego wykorzystano minimalną dawkę technologii.

Przechodząc na bardziej ogólny poziom – co uznałabyś za wyzwanie w pracy producenta?

Znalezienie dobrego scenariusza to zawsze wielkie wyzwanie. Scenariusz stanowi ważny etap produkcji i wyszukanie dobrego materiału sprawia mi największe problemy. Drugim wyzwaniem jest teraz pogoda, bo nie można jej kontrolować. Wcześniej wiadomo było, że jeśli potrzebna jest scena z pięknymi jesiennymi liśćmi w Nowym Jorku, trzeba ją zaplanować na koniec października czy początek listopada. Teraz jest to niepewne. Albo kiedy przyjdzie śnieg. Innym jeszcze wyzwaniem jest nadążanie za zmieniającymi się gustami widzów. Przykładem szybko zmieniających się upodobań publiczności są Chiny. Gdy realizujemy większą produkcję, okres przygotowań trwa jakieś sześć miesięcy, zdjęcia – cztery, a post-produkcja jeszcze rok. To prawie dwa lata. A teraz bardzo trudno przewidzieć, czy dana historia sprawdzi się jeszcze za dwa lata.

To stwarza problemy także w dystrybucji?

Cóż, teraz każdy jest zorientowany na Chiny. Nawet jeśli ktoś twierdzi, że dba o inne rynki, to bardziej deklaracje. Chiński rynek jest tak duży, że nie można go zignorować. Kiedyś przemysł filmowy w Hongkongu wystarczał, by wspierać realizację rodzimych produkcji. Stopniowo musiał zadbać o wpływy z rynków zewnętrznych. Ale teraz rynek chiński jest tak duży, że wystarczy pracować tam. Stał się dla każdego priorytetowy, a dystrybutorzy nie rozwijają już głębszych układów na rynkach takich jak Singapur czy Malezja.

Ciekawa jestem jeszcze, jak wybierasz filmy w które się angażujesz?

Przede wszystkim musi podobać mi się sam pomysł i scenariusz. Z założenia nie angażuję się w horrory, bo nie lubię ich oglądać. Czasem robię to bardziej na zasadzie zadania domowego. Nie sądzę więc, abym mogła wyprodukować film w tym gatunku. Powinnam też móc coś wnieść w projekty, których się podejmuję. Dawniej robiłam wiele filmów akcji, stąd napływa do mnie sporo propozycji z tej półki. Ale lubię też angażować się w małe projekty młodych reżyserów, ponieważ sądzę, że sama otrzymałam wiele pomocy na początku swojej kariery. Teraz dzięki moim możliwościom, znajomościom i doświadczeniu mogę pomóc takim reżyserom zrobić coś szybciej. Oczywiście z młodymi filmowcami pracuje się trudniej, bo nie są jeszcze uformowani i czasem sami nie widzą, czego potrzebują. Ale wówczas mogę służyć swoim doświadczeniem także pomagając im odkryć, do czego w ogóle dążą jako reżyserzy.

Nansun Shi

Producentka telewizyjna i filmowa. Założycielka firmy Distribution Workshop, która odpowiada za dystrybucję filmów takich jak "The Thousand Faces of Dunjia" Yuen Woo-pinga czy "Proste życie" i "Nadejdzie nasz czas" Ann Hui. Zaangażowana była też w produkcję m.in. "Lepszego jutra" Johna Woo, "Infernal Affairs" Alana Maka i Lau Wai-keunga, "Latających mieczy ze Smoczej Bramy" Tsui Harka. W 2017 roku otrzymała nagrodę Berlinale Camera, którą festiwal w Berlinie honoruje wybitnych producentów.